Episode 37. The National Security Toolbox Part I: 9/11 to Today with General Douglas Lute and Ambassador Marc Grossman

Has there been a “militarization” of US Foreign Policy since 9/11? General Lute and Ambassador Grossman talk about the aftermath of 9/11 & the war in Afghanistan- how the counterterrorism mission moved to a military/diplomatic campaign, negotiating with the Taliban while continuing the counterinsurgency effort, and... flying to dinner in Pakistan.

Episode Transcript:

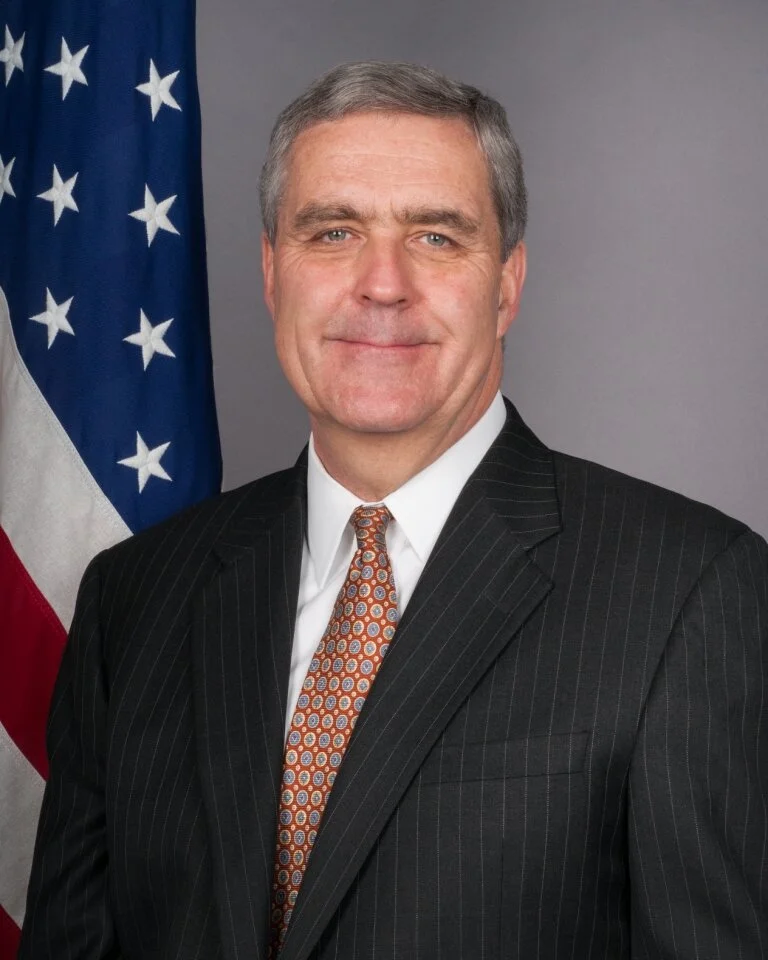

Amb. McCarthy: [00:00:13] From the American Academy of Diplomacy. This is the General and the Ambassador. Our podcast brings together senior US diplomats and senior US military leaders in conversations about their partnerships and tackling some of our toughest national security challenges. You can find all our podcasts and more information at the GeneralAmbassadorPodcast.Org. My name is Ambassador Deborah McCarthy. I'm the producer and host of the series. Today we are going to talk about the role and the missions of our military and our diplomats and how they have changed since 9/11. Our guests are General Douglas Lute and Ambassador Marc Grossman. They worked together for several years during the height of our engagement in Afghanistan. General Doug Lute served 35 years in the US Army. In 2007, he became deputy National Security Advisor to President Bush, coordinating the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He remained in the White House under President Obama until 2013. He then became the US ambassador to NATO until 2017. As a result, we call him both General Lute and Ambassador Lute. Today he is the CEO of Cambridge Global and among many other positions, he is a senior fellow in the Project for Europe and the Transatlantic Relationship at the Belfer Center at Harvard University. Ambassador Marc Grossman served 32 years in the US diplomatic service, including as ambassador to Turkey and as the undersecretary for political Affairs. He came back to public service after retiring to respond to a request from President Obama and Secretary Clinton to become the US Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, a post he held until 2013. Currently, he is vice chairman of the Cohen Group in Washington, DC. Gentlemen, thank you for joining the podcast series.

Gen. Lute: [00:02:04] Thank you for having us. It's good to be here.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:02:06] Much has been written, gentlemen, on the militarization of US foreign policy since 9/11. The Department of Defense expanded its non-combat activities into areas normally reserved for traditional diplomacy. It was given authorities and funding to carry out development and rule of law programs, for example, in Iraq and Afghanistan. General Lute. Ambassador Grossman, do you agree there has been such a shift and what did you observe in your time working together on Afghanistan?

Gen. Lute: [00:02:33] I do agree that there's been this perception of a shift. I think largely it was driven by the mission immediately post 9/11. I mean, it's understandable that when on a single day we lose close to 3000 Americans that the priority shifts to counterterrorism. And in the years immediately after 2001, that counterterrorism mission took on a very militaristic priority. The killer or capture mission strikes in Afghanistan and elsewhere around the world to try to suppress al Qaeda, because we're concerned about the next attack. Counterterrorism, in turn, passed in a way to a second mission, counterinsurgency. And again, here I think there was the primacy of military tools. This was largely driven, in my view, by the abundance of military resources compared to civilian resources. And even if you look at today, you know, the president's most recent fiscal year, 2021 budget came out, the DOD budget, the Defense Department budget is 15 times the State Department budget. So I think that budgets have come to reflect these two missions, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency.

Amb. Grossman: [00:03:35] Well, I'd like to agree with Doug. I think that makes a lot of sense and certainly is how I recall it. I think it's important to go back to the shock of 9/11. David Ignatius, the great Washington Post columnist and novelist, when he talks about this, says that what happened on 9/11 was so violent and so shocking that our gyroscopes got pushed over to one side. And I think there's a lot to that. And it wasn't just sort of military and diplomacy, but general gyroscope of where we were headed as a country. Our values got pushed over to one side, and it's taken some very long amount of time for that gyroscope to come back toward the center. I certainly thought in the days after 9/11 that there was going to be kind of more military effort. Maybe we let that go too far. But I would say also that if you look back at that time, there was an enormous diplomatic effort at the United Nations, for example, where resolution after resolution was passed after 9/11 that laid the foundation for some of the great fights against terrorism and the foundation for some of the counterinsurgency. Secondly, also, there was an effort to try to build a coalition around the world of people who were like minded against terrorism. And so, yes, it shifted. Yes, it should have shifted in some ways. But I don't think we shouldn't forget the diplomatic effort that went on at that time.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:04:52] General, you mentioned in an interview in NPR that in particular in Afghanistan, maybe it was over time, quote, We tended to over rely on military tools, on the military means, and we thereby counter discounted political, economic and diplomatic tools. Can you elaborate a little bit on this?

Gen. Lute: [00:05:11] I think this has to do with the basic design of our campaign or of our national effort in Afghanistan. And it goes to the fundamental question of the relationship between security and politics. There are two basic options. You can treat these sequentially. So first, you achieve security or attain a certain threshold of security, and that allows politics to take over. And in particular here I'm talking about Afghan politics. Or you can treat these concurrently. Treat them as though they're mutually reinforcing so you can make some gains on security, which then enable politics. The politics in turn produce a dividend on the security front and so forth. My observation is that we tended both in Iraq and Afghanistan to prioritize security. And because security was so difficult to achieve, we never really achieved that threshold of sufficient security to allow politics to kick in. And so we got, in a way, stuck in this quest for security. My observation is that we discounted the politics back to Afghanistan. The politics in Kabul itself, the politics between the Afghan government and the Taliban and the politics of the region. And I think we did that to some disadvantage to ourselves.

Amb. Grossman: [00:06:25] If I might say, I think that Doug makes a really good point. One of the things that really struck me in the two years that I was the special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, I was recalled to the government, and Doug was a great kind of leader and counterpart in that effort was when you sat around the table at a deputy's committee meeting, at a principals committee meeting, at an NSC meeting, it was natural that the president, the vice president, the senior leadership of our country was focused on the military mission because you had 100,000 young men and women serving in Afghanistan. And my goodness, if I'd have been just a plain citizen and I'd been sitting in that room, I'd say, well, somebody should be paying attention to my son or my daughter. And so there's a natural tendency, which I think was right to focus on that military side, because you have such an enormous investment in human life, in money, all those things. And it does it kind of distorts the conversation in a way. I think that's understandable. The point Doug makes and I think we together, I hope he would agree with me.

Amb. Grossman: [00:07:24] We thought a lot more in those couple of years about kind of a whole of government approach to Afghanistan. So if you think about Afghanistan, it's not just a military question. It's a social question. It's a political question. You know, when I would go to Afghanistan, I would sometimes stop and I'd say, what is it that Afghans need? Afghans need a job. Right? So that if you don't get the economics of this right, well, you're not going to make any progress on either security or politics. And so we tried as best we could to bring all these things together. If you think about President Obama's speech at Bagram Air Force Base in 2012 or the five lines of effort. Those five lines of effort tell you that what Doug Lute and a little bit me. We tried to accomplish was let's not make this just about the military. Let's make it five lines of effort. If you look at those five lines of effort, there are definition of what a whole of government activity in a country like Afghanistan could be.

Gen. Lute: [00:08:19] This should come only natural to the military listeners of this podcast because, you know, we're taught from the very early days that military conflict, military efforts are in support of political objectives. So this notion of subordinating the reverse, subordinating the military effort to politics should come natural. And the idea that the military effort should take priority, I think, should come to us as a little strange. And this goes all the way back to Clausewitz. What Marc and I tried to do in the years after the surge in Afghanistan ordered by President Obama was to. Enact the military campaign to the political and diplomatic effort in a mutually supporting way so that what you were doing on the battlefield actually had an impact with the politics in Kabul and actually had an effect on the potential to talk to the Taliban.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:09:13] Well, as you work together in the National Security Council. General, you were the deputy national security adviser. And Marc, you were the special representatives as you worked in the council, which for our listeners is the top team which advises the president on national security. Were there any major differences between Department of Defense, Department of State? And if so, can you give us an example or an idea of how the differences were resolved?

Gen. Lute: [00:09:37] Well, naturally, the departments tend to look at problems like the problem in Afghanistan through the lens of their experience. I think the first thing to appreciate is that the military and the State Department and the development world and the justice world all come at these problems from different angles, which are products of different experiences. Sometimes we don't even quite speak the same language about some of these problems. Whole set of different acronyms and so forth. So we come at these from very different angles. Typically at the national level, we were able to agree the national objectives. So the ends of the strategy, if you will. But we began, I think in my experience, to separate as we move from what we were trying to accomplish to how to accomplish it and the resources applied. So in the classic strategy model of ends, Ways and Means, the ends were typically agreed, but we began to diverge over ways and means and in means. In particular, the military means so overwhelmed the available resources of the other departments and agencies that you introduce some sort of distortion.

Amb. Grossman: [00:10:46] I think that's right. One of the things that I give Doug a lot of credit for, and again, I hope we made some contribution from the State Department, is that the personal relationships here, how you get along with the other human beings around that table is enormously important. And yes, when you sit at the table and your name is there and you represent the Department of State, and that's all very interesting and fun. But the idea is what's best for the United States of America. And at some point at those meetings, at whatever level, everybody has to say, I'm here not as a State Department person, but as an American and as someone who's trying to move this ball forward. And I think the way that Doug and others at the White House and I say we tried our best as well, was to set a tone that said we may have differences of opinion here. And boy, we certainly did on some very important subjects. But personally, we're going to get along and personally we're going to understand that everybody's got a job to do here and we can do it together. I mean, Doug and I spent hours and hours and hours, you know, flying all around the world together. Whenever I went to see the Taliban, I always had somebody from the White House represented there from the Defense Department, represented there.

Amb. Grossman: [00:11:54] So that we showed them that we were united, that we had this team effort. The other thing I think that's interesting is when you think back on the differences between big entities and, you know, they become quite personal. When I was the ambassador to Turkey, I had a large number of military people who worked for me, and I had two major generals on my country team. The major generals would come because they rotated quite often. And I'd say, you know, General, we're going to get on great. But at some point in our time together, there's going to be this clash. And I want to just alert you to why. And that is because what is the thing that you hate the most on the battlefield? Oh, they'd say ambiguity, right? It's ambiguity gets people killed. And I said, what's the thing that a diplomat likes the most sometimes? Well, it's ambiguity because it allows me to get on the next day to sort of get on with the diplomacy. And it doesn't make it right or wrong. But at some point, we're going to have this conversation about why won't you be more clear? And I'd say, because I need this ambiguity. And that was something that Doug and I talked about a lot and tried to work our way forward.

Gen. Lute: [00:12:53] So I remember long flights to and from the Central Asia region with Marc. And we would sit in these Gulfstream military government aircraft across the small table from one another and for 12 hours or so just stare at one another.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:13:09] You either bond or you don't.

Gen. Lute: [00:13:11] You either get along or it's a very much longer flight. And one of the terms that I take to this day from that experience probably now eight years or so ago, was this notion of constructive ambiguity. And Marc described to me exactly what he just described to your listeners, which is that on the one hand, the military seeks precision and on the other hand, diplomats value a little ambiguity, which opens up trade space, which opens up options and so forth. So I still carry around this. Grossman term of constructive ambiguity.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:13:42] Well, I would assume that you use some of this constructive ambiguity also is you were marked the first US diplomat to negotiate with the Taliban in 2011. Can you describe how not only the negotiations as you can share, but also the role that diplomats play in basically seeking to prevent, manage and resolve conflicts such as the one in Afghanistan?

Gen. Lute: [00:14:05] Well, first of all, my opportunity to have this conversation with the Taliban, of course, had been started by others, by Dick Holbrooke and some other people in the office in which I worked and had been worked over by people at the White House and at the Defense Department and national security. So when I took this opportunity on, I felt I had really the backing of really the US government to go and try to do this. And our effort was very important, I think, for people to understand not to negotiate with the Taliban, to make peace in Afghanistan. Our objective was to get the Taliban and the government of Afghanistan talking to each other about making peace. Know we talked about it, Doug and I and way we talked about it was our goal was to get Afghans to talk to other Afghans about the future of Afghanistan, that peace was for them to make. But we thought that if we could establish a series of steps, do this, do this, do this on both sides, that it might open the door for those negotiations. And if you see and we were talking about this a little bit before we started our program, if you see what Ambassador Khalilzad is doing now. Right. He may succeed in something that we both failed at. And I hope he does, because it's extremely important that some steps get taken so that Afghans start to other Afghans about the future of Afghanistan. My challenge was really 3 or 4 fold. One is on the side of the person I was talking to across the table. He and I had certain authorities and we had authorities.

Gen. Lute: [00:15:29] I thought, to do the job that we were supposed to do, which was to get these steps going and lead to some other arrangement. In the end, I think his job was to try to get Taliban prisoners out of Guantanamo Bay. And my job was to try to return Bowe Bergdahl, who had been a captive of the Taliban for several years before I started on this back to the United States. And what happened was that we ended up having a negotiation about prisoners and hostages rather than about anything else. And I think one of the good things that Zal has been able is, is that that's off the table now. He's been able to focus on more of the substance. That's the first thing. The second thing was I underestimated this. It turned out to be really hard to fight and talk at the same time. So I'm talking to this person representing the Taliban. And at the same time, the Taliban is killing American soldiers, Afghan soldiers, Afghan civilians. And so this is a very hard thing to do, is to fight, to call it a peace negotiation. It wasn't it was a series of steps hoping to get someone else to a peace negotiation. It was really hard to do. And then third, with Doug's backing, we were able to manage mostly the interagency effort back in Washington. But a lot of people were very uncomfortable with this negotiation, so a lot of it leaked out. People were opposed. It was hard to manage. And I give Doug and everybody senior to me a lot of thanks for supporting the effort.

Gen. Lute: [00:16:54] Marc understates his own contributions. I mean, if Zalmay Khalilzad is successful in moving us towards Afghan to Afghan discussions and Afghans are great deal makers, so our image was always, let's get the Afghan government and the Afghan Taliban in the same room and kind of count on their ability to craft a deal. But Marc, set the early steps in place, things like the exchange of some Taliban who had been held for years in Guantanamo in exchange for Sergeant Bergdahl was an early confidence building measure, the establishment of a safe place for the Taliban political representatives to represent the whole movement. This is the small office in Doha, Qatar. These are early steps which, if Zal is successful in the coming weeks, will be the precursors that allow Zal to move forward. And and he has taken some important steps and further prisoner exchanges, short ceasefires or reductions of violence. These are the sorts of small steps that lead to Afghan and Afghan talks. And they were actually put in place under Marc.

Amb. Grossman: [00:18:02] One of the things that you learn in senior service and government is nothing ever really finishes that you start to work on. And we tell senior people now that this is like running a relay race. So I got handed the baton to be the special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan. I ran as fast as I could, as most efficiently as I could. For two years, I gave that baton to Jim Dobbins, who passed it on, who passed it on. And here's Zell. I appreciate what Doug says. And you see some of your work kind of reflected in what happens down the road. And so your job is to do the best you can while you have the baton and give it to the next person.

Gen. Lute: [00:18:37] I'd also like to just come back on a point Marc made about how difficult it is to talk and fight at the same time, because this is the essence of the intersection between the military effort and the diplomatic effort. And this is enormously complicated because it happens on different planes. It happens here in Washington because the Congress doesn't always understand the intersection between fighting and talking. It happens among our allies and our partners diplomatically. You can imagine this is a conversation that NATO Council meetings. Right? So let me get this straight. You know, NATO allies might say and then it happens, obviously, in a country where the emotions are strongest because people are actually dying over these issues. So this is an enormously complex it really takes a military, diplomatic, National Security Council team that features mutual respect and open lines of communication to try to work our way through that. I'd like to think that especially when Marc was there at State, we had that kind of relationship.

Amb. Grossman: [00:19:37] And also, I think it's important to just go back to a previous conversation that we were having. You also have to make sure that you're paying attention to the economic aspects of this, to the human rights aspect, to this, to the regional aspects of this. I mean, Doug and I would go to Central Asian countries. And what were they interested in? Well, they were interested in the drug trade across their borders. So you had to do something about that, too. The Chinese at that time were just beginning the Belt Road Initiative. Well, it's turned into some enormous thing now, but at the time we thought, huh, I wonder if there might be possibilities of using that to help us in Afghanistan. And then very importantly and again, we spent a lot of time at this together. You know, you have to square up the close neighbors. You spent a lot of time in thinking about Pakistan. If you're trying to work on Afghanistan. We spent some time working on that as well.

Gen. Lute: [00:20:21] So the time with Pakistan is most poignant in my mind. By the tens of hours we spent sometimes literally all night with General Kayani, who was at that time the Pakistani chief of the army staff, probably the most powerful leader in Pakistan, who was at the controls of Pakistan's relationship to Afghanistan. He would invite us to dinner, which sounded very discreet, but dinner would morph into smoky all night conversations with legal pads full of notes in his boardroom, in his conference room, at his quarters. And there were some pretty long nights.

Amb. Grossman: [00:21:01] One of the things that also, in my recollection, you know, as we think about the job we were doing, we can't do our job unless you get supported from above. And at one point in this conversation with Pakistan, we went to our senior leaders, you know, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the secretary of state, the head of the CIA. And we said, we need you to fly, fly from Washington, DC to Pakistan to have dinner. That's it. That's that's what we need you to do. You know, the National Security Council equivalent there in Pakistan, and then you can fly home if you want or go someplace else. But what we need you to do is fly all this way to have dinner. And, you know, every single one of them did it. And we flew out on General Dempsey's plane. Right. And Secretary Clinton came and General Petraeus came. He was at CIA at the time. And there they were. And I thought to myself, this is what you want if you're in positions like Doug Lute and Marc Grossman. And that is when you need something from somebody senior to you, they say, sure, we'll fly to Pakistan for dinner.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:21:55] It's a whole of government approach. Everybody's involved.

Gen. Lute: [00:21:58] Marc makes an interesting point, but of course, it didn't fly on the same airplane. Right. We couldn't quite bring that off. No, no, that's right.

Amb. Grossman: [00:22:05] And we couldn't all go home on the same airplane. No, that's right. No, no, no, no.

Gen. Lute: [00:22:08] Everybody had his or her own airplane.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:22:10] Yeah. One day we'll do a podcast on the problems of transportation when you work for the government. This concludes part one of the general and the ambassador with General Doug Lute and Ambassador Marc Grossman. Stay tuned for part two. This has been an episode in the series The General and the Ambassador. Our series is a production of the American Academy of Diplomacy with the generous support of the Una Chapman Cox Foundation. You can find our podcasts on all major podcast sites and on our website, GeneralAmbassadorPodcast.Org. We truly welcome input and suggestions for the series. Please contact us at General.Ambassador.podcast@gmail.com. Thank you for listening.