Episode 64. Managing Adversity- Serving in Russia: A conversation with Ambassador Jon Huntsman and Admiral David Manero

Buses wait outside the U.S. Embassy compound in Moscow for departing U.S. diplomats. Photo: VASILY MAXIMOV/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

Former US Ambassador to Russia Jon Huntsman and former US Defense Attaché Admiral David Manero describe the effects of the large expulsion of US diplomats from Russia during a period of heightened tensions, their ground game to advance US interests in a hostile environment, Russia’s toolbox and offensive tactics and US actions to counter them.

Episode Transcript:

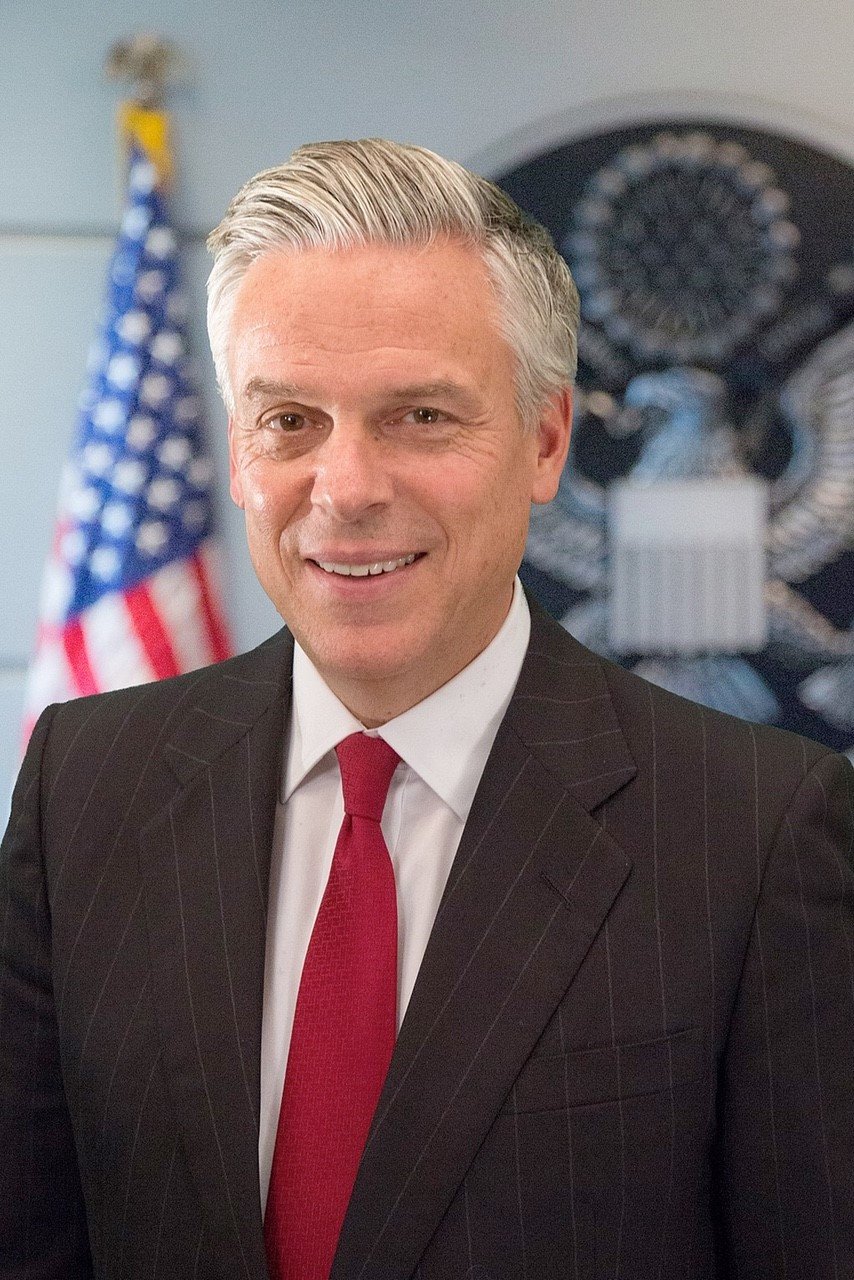

Amb. McCarthy: [00:00:15] Welcome to another conversation in the Academy of Diplomacy series, The General and the Ambassador. Our podcast brings together senior U.S. diplomats and senior U.S. military leaders in conversations about their partnerships in different parts of the world to advance U.S. foreign policy interests. I'm Ambassador Deborah McCarthy, the producer and host. The General the Ambassador is a production of the American Academy of Diplomacy in partnership with UMC Global at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Today, we will focus on U.S. diplomatic and military engagement with Russia. Our guests are Ambassador Jon Huntsman and Admiral David Manero. Ambassador Huntsman served as a U.S. Ambassador to Russia from 2017 to 2019. In his diplomatic career, he has served five presidents. He was the U.S. Ambassador to Singapore, the U.S. Ambassador to China, Deputy U.S. Trade Representative and Deputy Secretary of Commerce. Just prior to going to Russia, he was chairman of the Atlantic Council. He also served for two consecutive terms as the governor of Utah and was a candidate for the Republican nomination for president of the United States in 2011. Among his many, many activities today, he is also the chairman of the World Trade Center of Utah. And Manero served as a Defense Attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow from 2016 to 2018. He knows Russia well, having also been posted there as the U.S. Naval Attaché from 2011 to 2013. In his distinguished career, he made numerous operational deployments to the Middle East and the Western Hemisphere. He also served, among other assignments in the U.S. European Command as legislative assistant for the Senate minority leader and is a senior defense official at the U.S. Embassy in London. A warm welcome to both of you.

Adm. Manero: [00:02:08] Excellent.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:02:09] Thank you, Deborah. What a great pleasure to be with you and to be with the admiral

Adm. Manero: [00:02:12] Mine as well. My greater pleasure.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:02:14] Let me start with the following: as I noted, Ambassador Huntsman, you were the U.S. ambassador to Russia from 2017 to 2019. And, Admiral Manero, you served as the defense attache there from 2016 to 2018. This period of 2016 to 2019 was a very troubled time in the relationship. In late 2016, the U.S. intelligence community issued a report stating that Russia had meddled in the U.S. presidential campaign in response to the Obama administration, booted 35 Russian diplomats and closed some Russian embassy properties. In 2017, Congress imposed sanctions on Russia. In retaliation, Putin ordered 755 people cut from the U.S. diplomatic staff. The Trump administration, in turn ordered the closure of the Russian consulate in San Francisco. In 2018 following evidence of Russian use of a banned chemical agent to poison a former Russian military officer in London, the U.S. and other countries kicked out more Russian diplomats. In turn, Putin threw out 60 senior U.S. diplomats, including you, Admiral Manero, and Ambassador for your stewardship of the embassy. During this difficult period, you receive the Sue M. Cobb Award for exemplary diplomatic service. I know Sue, and it is an extraordinary award, well deserved. So I wanted to start our conversation by asking what it was like living and serving in Moscow during those tumultuous years with ever reduced staff.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:03:51] Well, Deborah, thank you. And it's probably important to note that Admiral Manero and I both got our start in Russian affairs, sitting in the same class at the University of Pennsylvania back in the early 1980s under the same Professor Alphonse Rubenstein. So we have common roots in that sense. My career took me more to Asia and China as a focus. And of course, Dave became one of the more prominent experts on the defense side and the US-Russia relationship. But you have to remember that the context in which all of this played out between the election, where the Russians clearly meddled in 2016 through our tenure there managing the embassy, it was an historic time. So let's just say we went from well over a thousand officers to down to about 455 when all of the carnage was settled. So to put that in perspective, I think you have to go well into the Cold War. If you can even find an example. I would cite 1986 with the arrest of Gennady Zakharov in New York City and Nicholas Daniloff in Moscow. That happened in August of 1986. The staff was cut in the aftermath of that to about 251, including all foreign service nationals, local Russians who were working in supporting us in the embassy itself.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:05:14] This was a function of taking what was a very active relationship, a lot of moving parts, a lot of operational details and cutting it by probably two thirds. So imagine getting the work of the United States done with a footprint that is way reduced, trying to figure out who to give assignments to. People were wearing two and three hats at the same time. I fortunately was able to take the baton from John Tefft, who was my predecessor and one of the most able diplomats of my generation, and did it in collaboration with people like Anthony Godfrey, who was my DCM and one of the very best in business. He was replaced by Bart Gorman, who was still there, another very able deputy. Imagine managing adversity, as I would describe it, and managing downside risk. That's what it becomes after a while, and you grow very tight within those embassy confines as a family. And that's where Dave and I and our families and the rest of the US embassy community became very close. You have no choice. You become each other's best friends and supporters. You're under siege day and night and living in truly historic times.

Adm. Manero: [00:06:31] As the ambassador was saying, it was really tumultuous times and they really were. It was a time of uncertainty. No one knew when they were going to get out or if they were going to be expelled, etc.. It seems like it's always a thing that hangs over your head. Day to day you wonder, will it be here tomorrow? Will we be here tomorrow? It's your family as well. It's not just the diplomats. They say 60 diplomats, but in fact, that's 60 families who have to hightail it out of there with dogs and cats and birds and pigeons and camels and whatever they happen to bring with them. But it was really quite a time to see all that coming together. And it's really a time for leadership and calm to steady the waters on our side and. Happy we had Ambassador Huntsman to do that. I think that the expulsion part was something that was very unexpected, I think initially because, as Ambassador Huntsman said, it really hadn't been done in a very, very long time. And it was perceived as a really extreme measure. But as this thing started to unfold, that was clear, that was going to be the path that was inevitable as we expel the diplomats from our side and they finally came over to the Russian side. It was quite a time to be there with family, to see my children wondering whether they'll be there.

Adm. Manero: [00:07:40] And then the night that had happened, when Ambassador Huntsman went over and picked the names up, I got on the phone to my wife and she had a whole house full of people. They all gathered in our house down there in the in the embassy compound. And as the names were read off, we read them off to them. And she was shouting to the people at the party, The Smiths are out, the Johnsons are out. And as this happened, it was like cheers and tears at the same time. So it's really a time of really mixed emotions. And in the end state, when we were flying out, Ambassador Huntsman came in and I mentioned this to him, This is a real point of leadership. It's the small things that become large. He went to the aircraft and shook everyone's hand on that aircraft, went around, and it was just a real sign of that togetherness that he just pointed out, that sense of family. It really was a sense of family. And as we exited airspace, they noted we were leaving Russian airspace and it was really spontaneous. The whole aircraft just picked up and cheered. And so it was like that weight was lifted off your shoulders suddenly in that one moment. But that's just kind of the flavor for the end game there.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:08:45] We lost the best and the brightest. The United States had had to send abroad officers who would spend decades steeped in the language and the politics and the economics had done multiple tours in Russia. So it's not just people we're talking about here. You're talking about folks who are the very best the United States had to send to Russia, and they were specifically targeted. Dave mentions the personal side, which is very real. People on the outside will read the headlines about the diplomatic spiral tit-for-tat between the United States and Russia. But it was a very personal undertaking. And I'll never forget the car ride over to the foreign Ministry. I knew the call was going to come and we were going to get responded to. So it really came in waves. The first wave was 755 people who were let go following our actions in the aftermath of the 2016 election meddling, where we kicked out 35 of their diplomats, we responded with sanctions as well, and the sanctions created enough anger on the part of the Putin team where 755 people were let go. And then came, of course, the poisoning of Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia in Salisbury, UK. That happened in 2018, the next year, and that precipitated the events that Dave has mentioned.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:10:07] And we all knew that there was going to be a response given what we did, which was 29 countries together in unison within 24 to 48 hours, disrupting significant GRU and SVR, Russian operations throughout Europe and beyond. I knew the call was coming any time, and it did one evening whenever the Foreign Ministry, it was cold and dark. And Sergei Ryabkov, the deputy foreign minister, handed me a manila envelope and I knew what was in it, and I didn't really read it until I got back out in my car. And I drove from the Foreign Ministry back to the gates of the embassy. And as I read each name, I thought, This is real, this is people, this is our ability to carry out and manage this very difficult and challenging relationship. And I called the team together in one of our rooms in the embassy, and it was jam packed. There were dozens of people there. I couldn't read the list myself. I was too emotional and I handed it to Anthony Godfrey. Dave will remember this, and Anthony went name by name, and as names were read out, you could hear sobs around the room and it became very real that they had days to pack their bags.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:11:24] Those of the 60 senior American diplomats who had been identified. And it was a horrible moment. But at the same time we were very tight as an embassy team and this pulled us together more than any other singular event in our commitment to one another to make sure that we would take care of our officers who were being kicked out. We would find replacement positions that would allow them to continue working in their professional environment to the best of our ability. And Dave handled it brilliantly with our attaché team, which of course was roundly targeted. Various sections specifically were targeted quite heavily. And I remember going home that night in the aftermath to my daughter Gracie, who was a college sophomore taking a gap year, working as an intern in one of the embassy sections because we didn't have enough people to go around after 755 had been dismissed. And I shared with her some of the names on the list, and she broke down and cried. And she's never forgotten that moment. That's how personal this event was and how it shook to the very foundation, the very core of our operating team at Embassy Russia.

Adm. Manero: [00:12:40] To the Ambassador's point, that crying part was really remarkable to see that release of emotions. And it was just the people getting kicked out. It was the people who were seeing those get kicked out. And it was also, believe it or not, our Russian friends, when you live in a country, you do make friends. And it's hard for people to believe that, oh, you're over in Russia, you're probably don't make friends. Well, in fact, there were Russians who were upset about this, too. And it was interesting to see their reactions as well, because, as the Ambassador said, a good slug of Russians lost their jobs initially and we were escorting them out of the building. And there were sobs on both sides. And when we finally got ejected as well, there was there were folks who were really emotional about this. It's amazing to see such a large event, such an international event, boil down to the personalities on the ground, because you don't usually get a chance to see that. And to Ambassador's point, the leadership from the top, that really struck a chord with everyone that you have to feel like you're part of it, you have to feel invested. And you could tell that was the case with every person who was there on station.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:13:41] Well, as you attempted to continue the mission, when to turn now to our National Security Strategy at the time and what it said about Russia, for our listeners, U.S. foreign policy priorities are outlined in National Security Strategies, which are issued periodically by the White House. The December 2017 National Security Strategy, issued by the Trump administration termed Russia not only a competitor but outlined in great detail Russia's aggressive behavior across the globe, including its military information and cyber operations. When you first arrived ambassador in Moscow, what were your priorities and what structures did you work through? As many of those of the paths were being dismantled, from what I gather?

Amb. Huntsman: [00:14:31] That's exactly right, Deborah. There was not much in the way of institutional connectivity between the two countries. Whatever had remained up until 2016 had been completely decimated in the aftermath of Russia's meddling in that election. And we were as flat as any relationship that I've experienced. And again, I've served in China during some difficult moments as well. So for us, it really was recognizing the nature of the relationship. It would be confrontational, it would be at moments cooperative where we could find those overlapping interests and it would be competitive. And for me, it was taking the traditional role of a United States ambassador, which is, number one, protecting American citizens within that country. Number two, reporting on events, whether it's political, economic or otherwise. Number three, you have certain national security objectives that you have to achieve even with a much reduced team, that's important for the United States to have. And then obviously, just keeping the lights on during such a difficult moment in relationship management and above all, avoiding broader conflict or war is always, of course, top of mind. And then you come to finding areas of common and overlapping interest. And we did have some of those. And we still do things like North Korea at the moment. It was one of their dangerous phases of weapons testing. Syria, the stakes, of course, in Syria, where Russia has played a significant role over the years, was something that we compared notes on. We had a deconfliction channel, which was very important part of our relationship that Admiral Manero can speak well to.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:16:19] We had issues around counterterrorism, Afghanistan, the Arctic, things like space cooperation. People don't remember that we relied on the Soyuz rockets to get our astronauts up to the space station, usually in collaboration with a Russian cosmonaut. So that was a very positive aspect of what otherwise was a spiraling out of control relationship. And then you had the whole basket of arms priorities, namely New START and what would be done around the corner in terms of extending the good work of New START, which was already a ten year old instrument, yet not complete, and much work that had to be done and what to do about INF, for example, which the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty, which goes back to 1987 between President Reagan and Gorbachev. Ground launch missiles that have the range of 500 to 5500 kilometers. We eliminated an entire category for the first time ever, the old Pershing missiles we had in Western Europe, the SS Twenties, the SS fours, SS fives and a cruise missile that the Russians had, of course, aimed at us. In 2014, the State Department alleged in their compliance report that Russia was in violation of this treaty and it got worse in the following years. And that became, of course, a major issue between us. So, Deborah, it ranged from everything from exploring space to arms control agreements to regional conflict in terms of finding areas of common overlap or areas where we didn't want to escalate conflict.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:17:56] Admiral, I want to ask you about your channels. You and your DOD colleagues, what channels did you have to speak to the Russian military in implementing these key elements of our National Security Strategy?

Adm. Manero: [00:18:10] I can tell by the Ambassador Huntsman's fulsome answer that it was very easy for me to talk security issues because he inherently understood them, and I appreciated that. And I think that made it a lot easier. So when he checked on board, he had mentioned to me that he had stopped in and saw the Secretary of Defense and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. And of course, that made my job a whole heck of a lot easier because he had a pretty good pre charge on the issues.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:18:36] And they both said you're going to be working with the finest officer we have serving abroad, Admiral David Manero. And I learned that to be the case, too.

Adm. Manero: [00:18:43] Yes, sir. I believe almost everything you say. But when Ambassador Huntsman came aboard, you talked about his priorities and you talk about the security issues. All of those were really stitched together pretty tightly because of, of course, the times they had just had the wonder weapons speech from President Putin. There were implications of that. There was a lot of saber rattling that went on. And for my part, the Ambassador mentioned and you mentioned the channel of communication. And I remember him saying to me, hey, listen, I spoke to General Dunford and we want to make sure that this is really a vibrant channel. We need to keep the communication open. When I checked on board there, we really made it a point to revitalize that channel. And it was with the Ministry of Defense, very controlled only with the officers, a few officers who are able to engage with foreign militaries. And I had a little pushback when I went back there because of my past being there before. And that's just natural. But it was really great to have Ambassador Huntsman on board to back that. Recall the time we went back and we had a meeting with Shoigu, and it was great because I was able to brief the ambassador on these security issues and because of his background, it was easy for him to understand that and what that did to the point of the channel, the one military channel we had open.

Adm. Manero: [00:20:04] It made it that much more robust. So it allowed me to have that channel open. And I saw the channel open up more and more. And it was a bit reluctant on their side. But it was important because, as the Ambassador pointed out, Syria was going on at the time, growing. The Russian influence there was growing, and it seemed that every time there was some movement on our side, I would get a phone call. And that was always interesting because I'd go over and receive the message and we'd have dialogue back and forth. But we set these channels in place so that at the time was General Dunford, the chairman, would have an open channel to Gerasimov and Shoigu so that we could prevent situations from occurring that might be misinterpreted, whether they be in Europe or up in the Arctic or down in Syria.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:20:48] Well, I wanted to ask also, when President Trump and President Putin met in Helsinki and they communicated periodically, John, how would you assess the relationship they had? And did this presidential channel help resolve diplomatic military differences?

Amb. Huntsman: [00:21:03] I would say, Deborah, that the relationship was so fraught, particularly with members on Capitol Hill, that it became very difficult to move in any particular direction. So any thought of convening something that was akin to the channel, a national commission, if you will, was an impossibility. So we had dialogue at the presidential level. Vladimir Putin is a master in terms of how he handles, deals with, and manipulates our leaders. He's been in office for over 20 years. He's met every leader around the world, knows every style of negotiation and factors out into his own strategy at the negotiating table. So it's really interesting. We go through players on a pretty regular basis. On the US side. That's where having core career diplomats in place as the backbone of our operations is so critically important. But the Helsinki meeting, the public messaging was a disaster based on some of what came out of the press conference. The meetings, on the other hand, were able to cover things like regional conflict, comparing notes on Afghanistan, on Syria, talking a bit about furthering arms control. So the behind the scenes meetings were fundamentally important in terms of coming to a common view on these issues. And you get to a point where only a president can articulate certain things on behalf of your country. So while the public messaging may have been challenged, there were important messages communicated as there typically are in phone calls and in sidebar meetings, say, on the sidelines of the G20 or other regional conferences. So these things are always important. But the backdrop, remember, was such a calcified relationship because of the tit for tat, because of the meddling, because of the ongoing cyber attacks where any flexibility or maneuvering room was made virtually impossible. So when I say managing adversity, I mean exactly that, managing adversity in the purest sense.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:23:07] For many years, Russia has pursued an ambitious military modernization effort, and while traditionally it's focused on the post-Soviet region, today, it operates across different parts of the world: the Med, the Middle East, North and Central Africa and the Arctic, which you mentioned. What is your assessment of Russia's military capabilities? Is some of this smoke and mirrors given Russia's generally weak economy?

Adm. Manero: [00:23:35] I think that it's a mistake to put too much into the smoke and mirrors theory, because behind some smoke there's fire and behind a mirror, you never know what's behind it. In this case, I remember when the Wonder weapons speech happened and the ambassador, we sat down and we talked about these things. And the Wonder Weapon speech was early.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:23:53] It was.

Adm. Manero: [00:23:53] March 27. Yes, sir. And I remember Ambassador came up to my office and as he was apt to do and I would be sitting there writing and this was quite a switch, I would just be minding my business at my desk, writing something down, and I would look up and there's Ambassador Huntsman, sir. He just popped into my office. We sat down and we talked about that and some of the stuff on there was some of the weapons were questionable that they have this kind of capability to have that kind of capability. And you're seeing now where the hypersonic weapons are now out and you're seeing this progress that have been made. So I would say that some of it might be a little smoke and mirrors, but behind it, there's probably a grains of truth that we need to pay attention to. You don't make those kind of speeches to your friends, right? You make those kind of speeches to your enemies, whether they're real or perceived or whether you need them, which in Russia's case, we're convenient enemy and they need us to be an enemy. I think that it would be a mistake for us to just push those things off regardless of the economy, because as bad as an economy can be, you can always channel a majority of your effort to those weapons that you really don't need.

Adm. Manero: [00:24:58] Instead of feeding the masses, you might channel it to to weapons. If I could just return back to the point the Ambassador made about the presidential engagement at the presidential level, I have to say that it was very challenging during that period to interact with my counterparts because, as the Ambassador said, Putin is not only a master at these manipulative things, it's kind of a societal piece. And if you're a diplomat there, they will try to manipulate you in ways that are subtle and in ways that are more overt. But the point is, is it made it very difficult to talk to my counterparts in uniform. But what it did, in a sense, was those channels of the Ambassador mentioned those basic channels that needed to stay open. Really, we tried to divorce those from the politics and kind of the the rhetoric and all the maybe tweets or anything else that was happening in the world and really focus on from a military to military perspective as to officers sitting at a table with uniforms on to discuss those matters that we knew were important to understand so that we could de-conflict. And that was really kind of my marching orders from Ambassador Huntsman as well as from our side in Washington.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:26:05] I think day brings up a good point. Beyond the headlines that were post 2016 election meddling, which was Russia all the time, we were running a real ground game in Russia carrying important messages, having meetings with key counterparts and interlocutors. Dave's messages were of the utmost importance from a national security standpoint that he was in discussion with. These were life and death kinds of discussions, deconfliction choices, and it was very real. So on one hand, you turn on CNN and it's all politics all the time, and on the other we're on the ground actually keeping the most fraught relationship alive and well from completely collapsing. And on top of that, it was virtually impossible, Deborah, to get high level support. So the thought of a Secretary of State, an Undersecretary, even an Assistant Secretary of State for regional affairs to make a visit to say nothing of Pentagon officials, which was absolutely an impossibility was extremely difficult. So we were managing things pretty much on our own, on the ground, communicating, of course, fully with Washington. But the support was it was extremely minimal simply because people didn't want to jump on a plane and show up in Moscow for fear of what Congress might do and that kind of environment for anything.

Adm. Manero: [00:27:26] Russia was third rail at that point. And so Ambassador Huntsman, I think having within Washington to my last point about Ambassador Huntsman having these appointments with these important people, it wasn't just show. It's that gravitas that we needed there to ensure that we were able to maneuver in that space. I think without that, if you don't have credibility on the ground, you don't have a ground game. I think, as the ambassador was pointing out.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:27:51] Well, as Russia was operating in these new theaters, what new alliances and partners helped the US address the global Russian military presence. I assume that on the ground you also work with your counterparts in discussing what Russia was doing beyond its traditional spheres.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:28:13] I spent a lot of time working with members of our Quad, which included our key allies in Europe, the UK being indispensable, Germany and France being extremely important players. So we would compare notes on a regular basis. We would instruct our capitals based on what we were hearing in Moscow and in fact we would coordinate as well based upon where Russia was most active in new theaters of influence and what to do about it, not unilaterally, but multilaterally with our friends and allies. And it was always apparent to me that Putin's goal was to reinvigorate Russia, to have it reflect more of the old glory days of the USSR. Of course, he was educated, grew up in his early professional years, took place during the Soviet era before the end of Empire, and I think he very much wanted to bring Russia back into that orbit, much more limited in terms of its capacity. Russia lost half its population, half its economy and a good chunk of its land size after the fall of empire. So Putin seemed to be working overtime and on the cheap to pick and choose his areas where he wanted to exert influence.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:29:31] And his toolbox was unbelievably diverse and so much different than anything we have in the United States, whether in Central Asia, whether in the traditional parts of Europe, where the old Soviet Union was prominent, whether in Central or North Africa or certainly whether in the Middle East, it was clear that Putin wanted to be a key influencer in parts of these regions. And he did, through a combination of gifts, in a sense, to these countries in which he was operating, whether it was security support, intelligence support, gas and oil cut rate deals on raw materials training, cash support, whatever it might have been. And he was able to in ways that still quite amaze me, work his way into key influencing relationships in critically important parts of the world. Putin could not be everywhere because the throw weight of Russia was far less than it was during the Soviet Union. But he was able to pick and choose in a very smart, strategic way, using a toolbox that was uniquely Russian, able to go in on the cheap and have his presence felt.

Adm. Manero: [00:30:40] I think no one knows these things better than our partners and allies over, you know, Finland and Norway. They understand they're close abroad. They've lived around Russia for a long time and they have a really deep understanding, as do the Europeans, for Russia's influence. And to your point, Ambassador, about what we did with our allies and partners, we had the Skripal piece happened and the United States was going to announce some expulsions. And you remember when we expelled diplomats first off and then our European allies all followed. It was that day and it was everybody was expelling people. And I remember that morning I got up and I checked my email. I was up early and sure enough, our Polish ally, they expelled first and I emailed my counterpart back and said, "Show off." And he laughed. He thought that was great. And later in the day I went down, I saw the ambassador in the morning and I said, "Sir, I think we're going to pull the NATO folks together." And he said, "I think that's great. And he said, Maybe we should add in some others like Ukraine, for example, and maybe we should." So we did. And I remember the reception we got. We had it at my home and we had them in the dining room, long dining room. And the response I got from that, sometimes you'll get a lot of people, but you won't get everybody. Well, we got everybody, plus all the allies and partners who were there, NATO, and they all came over and it was really a great feeling to see all those folks together. We were over at the embassy first and we decided to do it in the open spaces down on the first floor.

Adm. Manero: [00:32:06] And our Ukrainian partners were there and they were so proud that we had backed them up and our British partners were there and they were so proud that we had done this. The United States had taken that action, and it was really a binding moment.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:32:21] Russia has also been the source of a number of cyber attacks on the United States and or its allies over the years, some coming from the Russian government slash intelligence services, some coming from cyber criminals in the country. During your time, what channels did the US have to talk to the Russian government about these incidents, let alone cooperate on cybercrime?

Amb. Huntsman: [00:32:44] It was a little bit like my conversations with the Chinese in earlier years on their issues of intellectual property theft and their own cyber attacks, and it was complete denial. It was very difficult to frame the issue and have any kind of intelligent conversation about it because you have one party that would completely claim innocence that their outlaws, their bandits, their people who are out of the gambit of Russian government reach. And that would be about the extent of the conversation. This is an area that is critically important for us security and the security of our friends and allies, particularly in Europe. And it's one area where we really have to amp up our focus. The Russians are exceptionally good at cyber attacks and influence campaigns. You see it on a pretty regular basis. Again, they pick and choose their targets. They're very strategic and precise in terms of their end goals and the messaging. All the while we're always on defense, Deborah, and this is a big problem. The Russians are always on offense. And when you're on offense in the cyber world, you always win. You've always got the upper hand. So I know the security services in the United States and the new stood up Cyber Command are working on addressing this. But it isn't just a unilateral effort on the part of the United States. It's how we work with our partners in Europe who seem to be the recipients of a lot of these attacks and influence campaigns and how we can factor them into our responses as well. Collect the kind of information that would give us a heads up on operations before they're launched so we can actually make choices about what to do before we're hit. We're not yet to that level, but we desperately need to be.

Adm. Manero: [00:34:21] That's really 21st century full spectrum warfare. I mean, this is not the start of it because it had been happening before. To the Ambassador's point, it's just easy to deny, deny, deny, because and then even if you're caught, you say, well, these are just criminal elements and you keep pawning it off. And when in fact, what it is is just another rendition of full spectrum warfare. They've been good at this for a long time, influencing people. We didn't have social media before, but it was just the guy standing outside of maybe the hotel with a cigarette and you kind of recognized him. And that was kind of a signal to you better watch out. Well, it's these kind of influencers that are here now via social media and via cyber that can take down, you know, kinetic effects with non kinetic means, literally take down a banking system or destroy a dam or do something like this. And I think we're better positioned. Now to the ambassador's point about having CYBERCOM available to us and the different authorities that are now available to the United States to address these things.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:35:18] One of their grey zone tools is also disinformation slash misinformation, and they use it actively. I certainly saw it in my time in the Baltics. I note that in 2016 that the State Department's global engagement center was given the primary responsibility to counter disinformation abroad. But it's quite small and different combatant commands have set up their own disinformation hubs. What is your sense of U.S. capacities and capabilities in pushing back on Russian disinformation overseas?

Amb. Huntsman: [00:35:53] I think the Russians respond to only one thing, and that's force, and that's an able adversary who's able to punch back at the same level. And we traditionally have not been able to do that. One of their advantages is that they have a very slimmed down decision making bureaucracy, which is to say two or three people so they can say, "let's go after countries A, B, and C" with the following disinformation and disruptive messages and Putin gives the command to maybe Patrushev, who runs the National Security Council there, who can then pass it off to Sergei Shoigu, who passes it off to the GRU, and it's done. You can imagine in the United States, the bureaucracy and the time delay associated with any kind of significant action against another country. That is not a problem in Russia, so long as they are facile, quick in terms of decision making, we will always be at a disadvantage, notwithstanding maybe a technology, a superior approach to the problem set.

Adm. Manero: [00:36:56] It used to be just the Russian diaspora was a great entry point for them and it's gone beyond that now. You can project your message beyond that through the Internet. It can be not just thousands of miles away, but globally. And I think that they are well positioned to take care of that because the society has been like that for a very long time. The government kind of penetrating and controlling the message. And I think they're just better at that. And I hope in some ways we don't get better at that because that means we're slipping into kind of that authoritarian mode. But I think I hope we get better at countering that to to getting the truth out there so that we can expose these kind of nefarious messages and that we can convince people that we're the ones to believe.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:37:39] Well, we've imposed a lot of sanctions in response to cyber attacks and other actions. How effective have sanctions been in correcting Russian behavior and how did they adjust to them?

Amb. Huntsman: [00:37:52] Deborah, I would say that sanctions represent a very convenient weapon for the United States, particularly if you're a member of Congress, because if there is a very tricky problem set overseas or launched by an adversary, you go straightaway to sanctions. It sounds tough, it sounds immediate. And you can stand up in a town hall meeting and get an applause line out of it. The problem is sanctions are useless unless there is an ability to audit the results. I think sanctions are less effective if there is not an associated strategy. So what are we trying to do? What is the intended outcome and what is the associated dialogue? So sanctions without coupling it with a dialogue so you can actually walk Russia or name the country through the reasons for the sanctions, why they are there and what it might look like in terms of moving forward beyond sanctions. So we've never had that conversation with Russia. They've asked for it, but we have well over 1000 sanctions that are in place right now. Have they changed their behavior? Do oligarchs find it to be far more difficult landing their airplanes at Heathrow Airport, where sometimes they're impounded because we're on a sanctions list? That's a major irritant. But in terms of the bigger picture, I'm looking for a change of behavior on the part of Putin and his government. And I have seen no evidence whatsoever. So I would say sanctions can play a role. I think traditionally you can identify areas where they have. But let's measure the efficacy. Let's before we launch another round, let's make sure that we've at least accomplished our initial goal and achieved our intended outcome. Let's make sure that beyond that, we couple any sanctions with the dialogue to make sure that there is understanding on both sides in terms of where the relationship goes and where we might move going forward beyond sanctions. And then sanctions might have, I think, a more important role to play in terms of a tool in our arsenal. But right now they're all over the map with very little efficacy.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:39:54] I wanted to turn now to the relationship between Russia and China, which has grown in recent years. It's not a relationship of equals by any means. Russia's lost its empire and China is rebuilding or recreating its own. What is driving this increased so-called cooperation? Who has the upper hand and what does it mean for U.S. interests?

Amb. Huntsman: [00:40:18] I'll let Dave take a crack at that one first.

Adm. Manero: [00:40:20] So you just saw the recent activity in the South China Sea, this circling by Russian and Chinese ships in unison around Japan and coming within 12 miles of the coast because it's international waters. So it's really a remarkable development. There was always the question of we had Vostok when we were there, that was their operations that were together, Chinese and Russian operations together, how unified they were. There's always a question about how unified it was. Was it just a show that they were getting together? And I think we're seeing more and more of this activity because almost, you know, are we driving them in that direction or are they just taking advantage of a marriage of convenience, which I think is really probably the case? Because if you look at the history of Russia and China, there's really not a lot of love lost there in many ways. And there's still this kind of underlying suspicion that's there. But I think that the operations they've been working together are, if not real, they're at least now tangible. With this most recent exercise they had in the South China Sea. And I think it's something that we should pay attention to. It's just two countries who really are striving to have the links and alliances that we have worldwide to prove that, hey, we have friends, too, and we're each other's friends. And maybe Iran is our friend too. And so you kind of see how these players kind of mix it up and get together strange bedfellows. But I think that it's something we need to pay attention to, why it's happened, It's a sign of the times, how long, how enduring it is. Not really sure, but I'll stop there and let Ambassador Huntsman tackle this one because of his background.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:42:00] Dave's observations are spot on. This is a classic Putin move, and it's leveraging his own capacity and doing a jointly with someone else who brings complementary assets to the table. So let's just start with the premise, Deborah, that this kind of partnership between Russia and China should never exist. First of all, from our standpoint, I think it was a strategic miscalculation that we ever allow them allowed the relationship to form and develop and grow in the first place. We should have had more tools in our arsenal that kept them away from one another. Number two, history would suggest that the Russians and the Chinese have never done very well together. There is great distrust on the part of the Chinese toward the Russians, and the Russians tend to look down on the Chinese as being somewhat inferior in history would bear that out. So when I lived in Beijing, I lived in the Russian neighborhood, the urban park section of town, and I would travel regularly to the the Great Hall of the People. That, of course, was built by the Russians until they had a falling out in 1959, 1960. So the roof is built by, of course, Chinese architects and craftspeople.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:43:10] So it's a hybrid model between Russia and China. And every time I pull up to that building, it was a reminder to me that their relationship was never built to last. Of course, they had a major ideological falling out in 1960 through 1964 over Mao's Great Leap Forward and his interpretation of Marxism-Leninism, and they never again got back together again until the end of Empire, the early 1990s. So there is great distrust between them. But here here's kind of the way that I see it. It's an overlapping complementary relationship. When the two get together and both Xi Jinping and Putin see that as a bulwark against the United States, the Russians will handle the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea, the North Atlantic, the Eastern Mediterranean. They have strategic nuclear forces that are far superior to those of China. China brings the Indian Ocean, the Indo-Pacific region, an increasingly capable navy and an intelligence collection capability that is far better than what they had in earlier years. So, yes, they are trying to do exercises together. Dave and I followed closely at the first exercise ever, which Dave I think would have been 2018. That's right. 2019. And outside Vladivostok.

Adm. Manero: [00:44:27] That's right.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:44:28] We watched that exercise. There was no interoperability. They both watched each other. And it was almost like two military parades doing their thing. But I think since then they become far more advanced in areas that really do concern me sharing tactics, more interoperability than we saw in 2018, 2019, and certainly a lot more intelligence sharing between the two of them. So they're combining their platforms and they're making the calculation that the two of them combined can ably compete against the United States in any domain in any corner of the world. So that's their thesis, I do believe. And we'll see if they have the ability to turn it into anything beyond what is periodic exercises, meetings to share information and a lot of bluster and hype, which I know is of great concern to people who are following the story.

Adm. Manero: [00:45:21] Even in a world where we use the terms great power competition, who doesn't want to be a great power. So the way you prove your great power is to try to act like a great power and to be present. And this teaming up seems to be two of the great powers. We've bestowed that title on them almost by a fait accompli. And there we have it. So that's part of the driving dynamic.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:45:43] The unwritten story here is Putin never wanting to be the junior partner, but clearly he is the junior partner now. Xi Jinping is very deferential and very respectful, but Xi Jinping and his people know exactly what the limits to Russia's capabilities are, and they're using them just as the Russians are using the Chinese for every bit of advantage they can find.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:46:03] I wanted to close with one last question. Since your time in Russia, Russia has taken further actions to curb the work of U.S. diplomats in the country. In May of this year, the Kremlin declared the US being an unfriendly country, and in June it said it would end the 1992 Open Lands Agreement, which allows U.S. and Russian diplomats to travel freely in each country. This means that our diplomats will be pretty much confined to the embassy. Ambassador, I believe you said at one point, quote, If one weaponizes diplomatic expulsions excessively, diplomacy itself ceases, unquote. Gentlemen, where do we go from here in this relationship? How do we keep channels of communication open to prevent mistakes and keep the U.S. or in to advance its strategic interests?

Amb. Huntsman: [00:46:55] We have to have a clear cut and defined strategy. So what is it that we want out of the relationship that are tied to our national interests and our values? There's plenty there. We talked about it earlier in this podcast, and then we have to couple that with a level of engagement that actually allows us to talk to one another, not past one another. I'm a big believer in expeditionary diplomacy. I think that this is the one thing that has been lost in recent years. That is our great strength. The world loves our compassion as a country. The fact that we are real and we are transparent. And there's no better reflection of that than our diplomats who get out and about beyond the gates of what today are battlefield like embassies and connect with people. This is our magic as a country and where we have done so much for so many and improve the state of the world through our modern day diplomacy that now is threatened by security concerns and problematic relationships like what we find in Russia. So I would say we should continue doing what we've always done. Well, expeditionary diplomacy. But that must be coupled with a strategy and a level of engagement that allows us at the highest levels and the working level to connect on issues that really do matter. The alternative, Deborah, is that we become more and more estranged, and as we become more estranged, miscalculations become very real. And then the possibility of war, of course, is heightened substantially. So in the spirit of avoiding war and conflict, this is the down payment that our country should be making for the next generation to ensure that we can live in greater peace and harmony. It's not easy work, and it isn't easy to describe politically to your constituents back home when you're engaging with the Russians and the Chinese. But to my mind, it is an indispensable part of America's role as the sole superpower.

Adm. Manero: [00:48:54] And I'm just not a diplomat. And just to echo those great sentiments, you've just got to be present. You have to be invested. You have to take the time to interact and to engage. And, you know, our diplomats , you know, as a military guy I hear a lot of times, you know, “thank you for your service.” And my diplomatic friends, my friends who are diplomats and whatever agency they come from, particularly the State Department, I used to thank them just the same because they're out there doing that mission set and under conditions that are really challenging, maybe not wartime conditions, but sometimes war-like conditions where it's assault on your senses, it's an assault on your sensibilities as well. And so I really admire them for that and want to have that diplomacy part. General Mattis aptly said, "if you take away my diplomats, you'll have to give me a lot more ammunition." And that's true. War is not an extension of diplomacy. It's really an end state. That's really a tumultuous thing. And I think to try to avoid that, you have to be present and you have to be willing to engage.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:49:54] Thank you. It has been a great pleasure to talk with you and for joining our General Ambassador podcast. Thank you for sharing your experience. A difficult, difficult experience. Thank you for your leadership in a difficult time. We very much appreciate it.

Amb. Huntsman: [00:50:10] Thank you, Deborah. A wonderful pleasure to be with you and terrific to reconnect with that.

Adm. Manero: [00:50:15] Yeah, and my great honor, sir, again, to see you again. And Ambassador, thank you so much for inviting me to the podcast and both of you, a real honor to serve with you. And as I told Ambassador Huntsman, I learned a lot about leadership even late in my career from him. So I do appreciate that a great deal, sir. Thank you both.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:50:34] Our series is a production of the American Academy of Diplomacy in partnership with UMC Global at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. You can find our podcasts on all sites and on our website: www.GeneralAmbassadorPodcast.org. We welcome feedback and suggestions and can be reached at General dot Ambassador dot podcast at gmail.com. We do answer the mail. Thank you for listening.