Episode 65. The Republic of Korea: US Dip-Mil engagement during the Trump Administration with General Robert Abrams and Ambassador Harry Harris

General Abrams and Ambassador Harris discuss their partnership, the treaty alliance with the ROK, the shift under the Trump Administration to a top down approach to foreign policy and to a transactional relationships with allies, US summitry efforts with North Korea, managing ROK initiatives, the storming of the Ambassador’s residence, the threat of the PRC and the value of the Quad and AUKUS.

Episode Transcript:

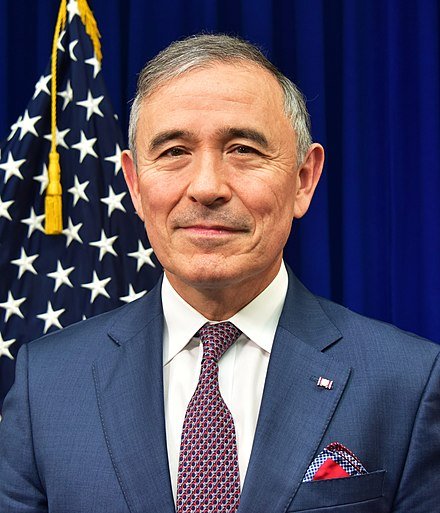

Amb. McCarthy: [00:00:13] Welcome to another conversation in the Academy of Diplomacy series, The General and The Ambassador. Our podcast brings together senior US diplomats and senior US military leaders in conversations about their partnership in different parts of the world to advance US national security interests. I'm Ambassador Deborah McCarthy, the producer and host. The General and The Ambassador is a production of the American Academy of Diplomacy in partnership with UNC Global at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Today, we will focus on US diplomatic and military engagement with the Republic of Korea. Our guests are Ambassador Harry Harris and General Robert Abrams. Ambassador and Admiral Harry Harris served as the US Ambassador to the Republic of Korea from 2018 to 2021. He had a long and distinguished career in the US Navy, during which he commanded the US Pacific Command, US Pacific Fleet, US Sixth Fleet, NATO's Striking and Support Forces and the Joint Task Force in Guantanamo. General Robert Abrams served as Commander, United Nations Command, Combined Forces Command and US Forces Korea from 2018 to 2021. Just prior, he served as Commander US Army Forces Command. In his long and distinguished military career, he commanded from company through division level, including combat operations in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq and Afghanistan. Gentlemen, thank you for joining the general and the ambassador. It's a pleasure to see you both. And I know it took us a while to coordinate schedules and times. Ambassador Harris, General Abrams, you partnered as the US diplomatic military team in the Republic of Korea for over two years from 2018 to early 2021. Before we dive into the specifics of your work on the ground, I wanted to ask at the outset two questions geared to some of our younger listeners. We ended our presence in Iraq and we've now withdrawn from Afghanistan. Why is it important for the United States to remain militarily present in South Korea 70 years after the Korean War?

Gen. Abrams: [00:02:27] First thing I'd say is that the Korean War, I think for all the listeners that can understand the Korean War is not over. We ceased hostilities in 1953 under an armistice agreement, and both sides agreed to cease hostile actions. We stepped away from each other, established a four kilometer buffer zone across 250 kilometers of the Korean Peninsula. And we maintained that armistice until today. And as the armistice agreement said, until a permanent peace could be established. And here we are 68 years later, and we still don't have a peace treaty. And our US military physical presence in Korea, albeit very small, about 28,500 or so, it serves as an unmistakable deterrent against any potential North Korean miscalculation or misunderstanding that we remain to the defense of the Republic of Korea. The second thing I'd say is the United States and the Republic of Korea in October of 1953 signed a mutual defense treaty. And for the younger listeners, that is a Senate ratified defense treaty whereby we, the United States, promised really two things. One, that we, together with the Republic of Korea, would deter any further aggression against any armed attacks. And if there was an armed attack against either of the Pacific area, that we would respond to each other. This treaty was established so that and I quote the treaty, "no potential aggressor could be under the illusion that neither the US or the Republic of Korea stands alone in the Pacific area." Those are probably the two biggest reasons. The third one that I like to add, and I know Ambassador Harris feels very similarly, is our relationship might have started in the shared hardship and blood lost in the Korean War, but now it's a relationship of shared values and the Korea and the United States have much more in common today than we had 70 years ago.

Amb. Harris: [00:04:29] I'll add on to that by associating myself with everything General Abrams said, and I'll add to it. We are in these countries for our interests, for American national interests, and I think that's an important point to make. A recent survey said over 60% of Americans support the alliance and support us defending the Republic of Korea should it fall under attack. And over 80% of Koreans support the alliance and support the treaty that we signed with the Republic of Korea in 1953. So this is not a fly by night relationship. It is a significantly important relationship to the United States and to the Republic of Korea.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:05:14] Several months ago, we did a podcast with Ambassador Mark Lippert and General Vince Brooks, and we discussed the major issues in the bilateral relationship during the Obama administration. In broad terms, how did the relationship change or evolve under the Trump administration?

Amb. Harris: [00:05:32] I served in the Obama administration when I was the PACOM, now INDOPACOM Commander, about a year left in that tour, I served in the Trump administration. President Trump Beforehand, President Obama were my commanders in chief when I was in uniform. And then when I went to Korea, I went there as a Trump administration political appointee. I retired from the Navy on the 1st of June, and three days later I was in Washington for the ambassador seminar. Four weeks later, I was confirmed and I was on my way to Korea. I think that the difference thematically between the Obama administration and the Trump administration's approach to relationships with countries is the the Obama administration and now the Biden administration places great emphasis on alliances. It's a welcome approach, in my view, than the Trump administration's approach, which was more transactional. And I think we saw that play out in Korea in ways regarding the special measures agreement and the burden sharing defense cost sharing agreement. Now, to the Trump administration's credit, I think that their view of the threat from the PRC was more accurate, if you will, than their previous administration's view on the PRC. So the Trump administration recognized that the PRC is our competitor. They didn't go as far as to say they are adversary, but they went as far as to say that they are our competitor. And today we see the Biden administration taking that same tack. Secretary Blinken in his confirmation hearing said that the previous administration's approach to China is right, that what's happening in Xinjiang is genocide and that human rights are being trampled in Hong Kong. Secretary Austin at his confirmation hearing, said that the PRC was the pacing threat and he was going to pay attention to it and he promised greater support for Taiwan. So I think that the Trump administration's view of the People's Republic of China was spot on. I think their view of alliance is, in my estimation, that view is wanting.

Gen. Abrams: [00:07:33] I think it's important for your listeners to understand we have seven treaty alliances and we're part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. We have broad interests and treaty alliances around the world and responsibilities around the world. How the relationship changed is Ambassador Harris just outlined. The Republic of Korea has one treaty alliance. They are all in with us. And so when you saw the change in the Trump administration, as Ambassador Harris said, very transactional. That comes as a shock to a country that only has one treaty alliance and that they put so much stock and energy and whole of government approach to engagement. And now suddenly their alliance partner has changed their method and modus operandi. So that's certainly added additional stressor to the relationship. The guidance given to me that the concern was, hey, we've been down this road before with North Korea, so we need to continue to maintain a high level of readiness while simultaneously preserving space for diplomacy. So the guidance I received in November 2018 as I headed to Korea was pretty simple. One eight Figure out a way to maintain your readiness, the readiness of the combined force while simultaneously preserving space for diplomacy. Be creative, Be innovative. And we were able to do that, and I'm happy to talk about that. The second piece of guidance was pretty straightforward also, which was don't make any news. And that's important because the methodology under the Trump administration for engagement was top down, not bottom up. So when you have a top down approach like that, it's important for everybody below that to sort of follow the lead of where that top down diplomacy is coming from. And there had been some blips in a variety of different places up to that point. And Secretary Mattis was pretty clear. He said, hey, look, just stay out of the news, go about your business quietly and stay out of the newsU

Amb. McCarthy: [00:09:49] Speaking of the top down, I wanted to turn to our engagement with North Korea during your time and South Korea's engagement with North Korea. On the US side, the president held three meetings with Kim Jong Un in Singapore, in Hanoi, and in the demilitarized zone along the 38th Parallel in 2019. How did you each work with the government of South Korea in the preparations for these high level engagements to manage their expectations as our president was so deeply engaged?

Amb. Harris: [00:10:22] I wasn't around for Singapore. That happened in 2018, two days before my confirmation hearing. So I had already left PACOM and I was in my preparation to go be the ambassador. So that's when Singapore happened. So I can't take any credit for it. And I will say that was the best of the three summits that involved President Trump and Kim Jong Un for the Hanoi summit that was in Hanoi. And the embassy's role was to facilitate dialogue between Washington and Seoul, between the Blue House and the White House. But the nitty gritty, the minutia, all the specifics of the summit was handled directly by the advanced teams and all that. And we had the United States, we had a designated special representative for DPRK, Steve Biegun, who was also the Undersecretary, fantastic individual and did a great job. South Korea had their individual ambassador, another terrific individual. He and Steve worked together extremely well, and they were able to craft what I thought was a pretty good arrangement for Hanoi. Unfortunately, Kim Jong-Un did not take advantage of this really great opportunity that North Korea was presented in Hanoi. He did not take advantage of that. And because of that, the Hanoi summit failed, but it didn't fail for any reason that can be laid at the feet of the United States or the Republic of Korea. It failed because Kim Jong-Un wasn't willing to do what he said he was going to do in Singapore.

Amb. Harris: [00:11:57] And then the third summit was the summit at the DMZ, the Snap Summit, if you will, the Twitter summit. And that one, the embassy team. So was deeply involved because it happened so quickly. So it fell to us to do the arrangements. And we relied heavily on USFK, General Abrams and his team for all the logistics piece of that associated with the political part of the president talking to the troops, but also all the logistics. I will say that it was because of President Trump's unique style and his out-of-the-box thinking that allowed the so much to happen in the first place. He just reached out on his own, more or less, to Kim Jong-Un and suggested they get together and just put this thing in its right box. After the "fire and fury" of 2016 and "Little Rocket Man" of 2017 and all that, the fact that they got together in 2018 in Singapore was not insignificant. And they did it again in Hanoi and they did it again at the DMZ. So that's the value of top down. But ultimately you need these things to be staffed, in my opinion, diplomatically between diplomats, between the experts on both sides, between the North Korean side and the American side, keeping our South Korean ally in the loop. And that didn't happen. And we are where we are today with a different approach by the Biden team.

Gen. Abrams: [00:13:19] Like Ambassador Harris, I arrived in November of 18, so I was not there for Singapore, but I was certainly there for Hanoi. But most important for me was just understanding the US position prior to Hanoi and then being able to keep my Korean counterparts in ROK JCS and ROK Ministry of National Defense informed. And this is where the really tight relationship between Ambassador Harris and myself was so critical. And we were constantly comparing notes, sharing updates that we had received through our respective channels to be able to make sense for it for our counterparts. And from a military perspective, for Hanoi, I'll just share that there were high expectations throughout the Republic of Korea for that Hanoi summit for a breakthrough agreement, and it permeated everything in the military domain and required constant reminder from me and the ROK chairman of the importance that we needed to maintain an appropriate level of readiness. My point was there was no certainty associated with summit results and we should be careful to manage our own expectations. There was career concern on the Korean side and frankly with me that President Trump might cancel exercises again. That's one of the things he just extemporaneously at the Singapore summit. And the significance for us was we were literally two days away from starting our semiannual theater level exercise. In fact, we were on our fourth day of crisis management staff training that we do as a precursor prior to the beginning of our semiannual training.

Gen. Abrams: [00:14:54] So there was a lot of concern he was going to cancel it. The concern was it had been a year since the Republic of Korea and the US military alliance had conducted one of these theater level command post exercises. And so people say, "So what? It's a year. You guys have been practicing this for 70 years. How could it be so hard?" People have to understand that in the military domain, not only do the US service members change out about 50% of our staffs every year. But the Korean military changes out their senior staff on a frequent basis. So at that point we had already had 60% turnover on our Korean staff. Korean members of the CFC staff, as well as the ROK JCS and about 50% of the US personnel. Had we not gone through with that combined command post training theater level exercise, by August of 2019, we would have had 100% turnover. And this was my message back to Washington and sharing through Ambassador Harris about the importance of please don't allow exercises and our combined training to get on the table because it would have a significant long term effect on the alliance.

Gen. Abrams: [00:16:11] The only thing I'd say about June 29, 2019, the summit up in the joint security area inside the demilitarized zone. My role not only as US forces Korea to provide US military support of that, but was also the role of the United Nations Command established by U.N. Security Council Resolution 84 in July 1950. That command still exists today as the only signator of the armistice agreement representing forces on the south side of the military demarcation line. And today, the United Nations Command has direct oversight and authority of the joint security area that we share with the North Korean army, the Korean People's Army. I think what's significant here for your listeners would be to know that how did we pull that off after a tweet at about 830 in the morning, our time from Japan? It's about relationships. And I'd start with the relationship with then Special Representative Steve Biegun, who I had met previously and we had a great relationship with. He he actually texted me on the phone with a, "Hey, can you guys get a message to the North Koreans?" "Sure. We have a hotline with the North Koreans up in the joint security area. We make two line checks a day. Send me your message." They texted me the message. I cut and pasted it into an email. I sent it to our United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission Secretariat, and I said, "Hey, get this delivered to the North." And by 2 hours later, the North Koreans came out with a statement saying, "Well, we'd be interested."

Gen. Abrams: [00:17:51] And so, as Ambassador Harris indicated, the other relationship I'd say that made it happen was because over the previous seven or eight months of disarming the joint security area and demining the joint security area, our UNC Security Battalion Commander, a US Lieutenant Colonel and his KPA counterpart, they had developed a working relationship. They had built basic levels of trust and we were able to then early the next morning, set up a meeting for the appropriate security officials and Secret Service and so forth to be able to do their business. So all of that to say in direct support of creating the conditions for President Trump to meet with KJU in the North. The last thing I'd highlight there was some awkwardness, as Ambassador Harris and I were together during that trip up to the joint security area and up to the DMZ. And the awkwardness came in that and this is about style. President Trump had not invited President Moon to the meeting, and that that did cause a bit of an awkward moment. President Moon was there in the JSA to greet Kim Jong-Un, but he was actually not in the meeting, and that was widely reported in the public space. That did make for some awkwardness, but we were able to overcome it.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:19:06] I wanted to shift to understand a little bit more the South Koreans relationship with North Korea, because before they too had summits, they signed some agreements. They opened up a liaison office, even though the North blew it up later on. And as I understand it, in their pursuit of their own relationship, a couple of issues come up, which is their desire to have some sanctions or sanctions ease to be able to get the North Koreans to engage. And also the issue of pursuing an end of war declaration to improve North-South relations. I wanted to get your views on on, let's say, on the sanctions first. How did you manage the differences on keeping the sanctions on, which is a strong US and international position versus what the Moon administration was trying to do at that time?

Amb. Harris: [00:19:57] To begin with, you said spot on, Ambassador. The sanctions weren't American sanctions. They're not US unilaterally imposed sanctions. There are some of those. But most of the sanctions, certainly the really hard sanctions, which in my opinion contributed to bringing North Korea to the negotiating table in the first place in Singapore, the sanctions are United Nations sanctions. And so it requires all of the permanent members of the Security Council to agree, because each one has, as you know, veto on that. So the fact we got sanctions at all, and as tough as they are, is a testament to the power of the United Nations in this way. And so you're right that the South Koreans wanted to do a lot of inter-Korean projects, that they could move forward with their relationship with North Korea. And President Moon and Kim Jong un had their own cemetery. They had three independent presidential summits, just like President Trump and Kim Jong Un had three summits. But all of those, not all of them, but most of the initiatives that the South Koreans wanted to move forward with the North, came up against the sanctions. They came up against United Nations sanctions that were agreed upon by the U.N. Security Council and were manifested through a U.N. Security Council resolution. And so my job was to tell them they couldn't do that. That was a hard thing for me to do. It was easy for me to do it, but it was hard. It was a hard issue. I would have a meeting and before at the Foreign Ministry, which the building is directly across the street from the American embassy. When I say street is, it's eight lanes of traffic in a center park thing. It's just across the street from the embassy. I go to the Foreign Ministry, talk to the Vice Foreign Minister or the Foreign Minister. And by the time I got back to the American embassy, the thing had already been leaked in the press. So I was pretty frustrated by that. Or I'd go to the Blue House and I would talk to a national security adviser and the thing would often be leaked. So that was frustrating. Here's an example, of I'll hold it up here so you can see it. It's an example of a cartoon that showed up in one of the Korean dailies, and it says that I oppose inter-Korean exchanges. Burden sharing should be greatly increased and South Korean forces should be dispatched immediately. That was a request that we had for South Korean military, their navy, to support our efforts to keep the Strait of Hormuz and the North Arabian Sea free of attacks by Iranian forces after a South Korean merchant ship had been captured by the Iranians. So you think that would be an easy sell? So my job being ambassador is to deliver these messages from the White House and from Foggy Bottom to the leadership in the host nation, South Korea, in my case. And buck up when they hit you back with things like this or when they stormed over my residence and Seoul.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:22:59] General, I'll give you a chance to interject here.

Gen. Abrams: [00:23:03] Ambassador Harris and I spoke frequently. We're in constant contact, and that's important for me as the senior US military officer in Korea and the day-to-day representative of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs to the ROK JCS and to the Ministry of National Defense, to have a clearer understanding of US policy so that A, I remain aligned with that policy. And it was fast moving. I couldn't wait for a readout from a deputy's meeting or a principals meeting that would filter its way through the Office of the Secretary of Defense, etc. I was getting it in real time from Ambassador Harris, and that was so important for me, principally, I'd say, as the United Nations Command Commander, because many of these initiatives by the Republic of Korea were going to require crossing the Military Demarcation Line to deliver said aid to North Korea. And again, as the UN Commander responsible with and given the authority for civil administration and relief of the DMZ and no one can cross the MDL without my approval, it put UNC in this interesting position. UNC doesn't enforce sanctions. That's not their job. I enforce the armistice agreement, but the frustration when these initiatives would run up against sanctions and sanctions concerns, then we have to blame someone.

Gen. Abrams: [00:24:27] Sometimes they would blame Ambassador Harris, but other times they would just blame US policy. At other times they would confuse the issue again in the media and say, "Oh, this is the United Nations Command that's blocking these initiatives," and that could not be further from the truth. And there's a couple of notable instances. They wanted to connect an inter-Korean railway. This has been a longstanding desire, a plan had been agreed to for them to go forward with that, but it had to be reviewed by the 1718 committee and that took time. It doesn't happen overnight. Once it was approved by the 1718 committee, we received a request to the United Nations Command. It was approved in less than a day, and eventually it was conducted in December. Some of the narratives kind of got confused. But I guess my message for your listeners would be it was necessary for Ambassador Harrison and I had these close communications so that I could stay tuned in on what was the latest position on where we were and what initiatives were being pursued and what was not going to be acceptable.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:25:27] I wanted to jump back to the storming. Can you tell me, Harry, about the storming?

Amb. Harris: [00:25:32] This was centered on the SMA, the Special Measures Agreement, the burden sharing, the defense cost sharing agreement. When our side asked for a significant increase in contributions by the South Korean government. The purpose behind the agreements globally is to help defray the costs of stationing US forces in countries whose purpose the forces are to defend that country. The South Koreans have been paying $800 million a year, but the Trump administration asked for a significant increase. That was a hard pill for the South Koreans to swallow. And to be honest with you, they did not swallow. There was a lot of angst and a lot of resistance from the South Koreans, and it spilled over into their demonstrative society. South Korea is a very demonstrative nation. They believe in democracy and they are very demonstrative. And so we had protests around my residence, which was separated from the embassy by a mile or so. There were protests around the embassy. There was a "decapitate Ambassador Harris" downtown on that big square I was telling you about the separated US embassy from the Foreign Ministry, and then they had about 20 protesters. Students stormed over the walls. They went over the wall of my residence, which is very high walled, guarded and all that place.

Amb. Harris: [00:26:54] And they stormed over the wall and they rushed up to the residence itself. It's a large compound, but they made it to the front steps of the residence. I was coincidentally at the Blue House at a reception hosted by President Moon, and my wife is in the States at the time and my house staff, their job is to make the perfect drinks and the perfect canapés for the receptions we have. Their job is not to defend this house, but two of them did in fact defend the house. They were injured in that process. So that was what happened as an outcome of the resistance for the burden sharing agreement for their ask by the US government at the end of the day. Four of the students that went over the wall were given prison sentences, found guilty and given prison sentences. Those sentences were suspended, but they were found guilty and South Korean court of law. So that's important. And it's just part of the adventure of being an ambassador. My predecessor, Mark Lippert, was almost killed by a left wing protester while he was attending some kind of a civic event where he required 80 stitches in his face. And he's got permanent damage in one of his wrists.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:28:05] Well, I wanted to turn to another issue in terms of South Korea's rapprochement, efforts at rapprochement with the North, which is the issue of pursuing what is called the end-of-war declaration. What would such a declaration mean and what has been the US position on the issue?

Gen. Abrams: [00:28:22] I'll accept what has been said publicly in that it would be a symbolic gesture only in terms of its meaning. Here's my concern, and I've said this in several forums. I'm concerned how such a declaration might be interpreted and twisted by some to justify requests for the United Nations to act, to start taking action to rescind U.N. Security Council resolutions from 1950, and specifically UN Security Council Resolutions 82, 83 and 84, which are still in effect today. If the war is over, I think there will be legitimate questions as to the rationale: Why do we still need a unified command? I said this earlier in the podcast. That unified command was named United Nations Command. And the significance of that is the United Nations Command is the sole signature representing the forces on the south side of the demilitarized zone. And if there is no unified command, let's say that we don't need a unified command. If there's no unified command who's now responsible for the armistice agreement. And I my concern is I think we run the risk of going down a slippery slope of backing into a peace agreement. And yet we have still not made any progress, one step of progress on denuclearization.

Gen. Abrams: [00:29:48] And if the war has ended, then does the alliance still need Combined Forces Command? Combined Forces Command was specifically established in 1978 to defend the Republic of Korea from North Korean aggression. So if the war is over, then we don't need CFC. My concern is I think we need a clear agreed to bilaterally agreed to strategy which includes an agreed upon end state before we begin pursuing specific ways to get there ends ways and means the three essential elements of a strategy. An end-of-war declaration is one way. That's a way. It's not the only way. You ask, What's the US position? I think what we're seeing playing out diplomatically in the open press is I don't think we have agreement yet on exactly what's that end state and then what's the sequencing. And and this has been a big debate topic for the United States and the Republic of Korea for 30 years, and that's the sequencing. Does denuclearization happen first, then we go to peace or do we have to establish a peace regime first, establish a peace agreement and then go to denuclearization? I think that's the fundamental friction point where we are.

Amb. Harris: [00:31:11] I'll add to what General Abrams said, the difference to the average person between an end-of-war declaration and a peace treaty, that difference becomes like a nuanced difference. It's hard to explain what is an end-of-war declaration if it's not a peace treaty. And so it's not a peace treaty. The war is still on, the armistice is still. But it's going to be hard to explain to people. You just signed this piece of paper, this declaration that the war is over. It's hard to explain it to the average American and it's hard to explain to the average South Korean. And I believe the PRC and the DPRK will jump into that scene in a big way. So how I've characterized it is this. What changes the day after an end of war declaration is signed? The armistice is still excellent. The US treaty obligations to defend South Korea remain extant. And North Korea's considerable nuclear, conventional, chemical, biological forces remain extant. What good is it other than a feel good? I say it half tongue in cheek. But we already have an end of war declaration. It's called the Armistice Agreement, and it served us well for 70 years. So let's do all the things necessary to have a peace treaty to actually end the war between between the North and South and United States and all of that with all the parties involved that are involved in it. Let's get to denuclearization of North Korea and let's do these things that that both governments, the North Korean government and the US government agreed to in Singapore, which at the end of the day, if all the measures are implemented, will actually give North Korea a brighter future for its people. So let's do those things, but let's have some halfway measure which on the surface makes everyone feel good but in reality contravenes peace on the peninsula.

Gen. Abrams: [00:33:20] Some people may ask why the armistice agreement? Why is that so important? The armistice agreement is the only internationally recognized legal instrument that has prevented the restart of hostilities on the Korean Peninsula. That is significant. And as Ambassador Harris indicated, an end-of-war declaration not legally binding. And I think both governments have said that publicly now. But in the eyes of the world, there will be a lot of questions as to why not? Why isn't it legally binding? And it certainly has the potential to take on a momentum of its own and then back its way in without any international legitimacy and the endorsement by the United Nations.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:34:04] I wanted to turn to China and its role in the Korean Peninsula today. China, South Korea's most important economic trading partner, though it does use that as a choke hold on occasion. Still, South Korea has said it will not take sides in US-China rivalry. And President Moon has invited Xi Jinping to visit. Where do the US and South Korea agree and disagree on China? And how did you manage the disagreements?

Amb. Harris: [00:34:33] Let me back up just one step and just say that the US and the PRC and I'll make a distinction when I talk about China, whether it's the PRC or Taiwan. So we're really talking about the People's Republic of China or PRC. So let me just take one step back and say that we have as a nation, we have partnered well with the PRC on a number of important fronts. The PRC government simply doesn't keep its word from its treaty with the British on Hong Kong, to its human rights abuses against the Uyghurs and many others to the level that Secretary Blinken has called a genocide, which is a trigger word in diplomacy as well to its attempts at commercial espionage in its quest to first isolate and then dominate Taiwan. So we fundamentally disagree with the way ahead on the globe with the PRC. South Korea is trying to have its cake and eat it, too, So its number one trading partner is the PRC, but its number, its only security ally is the United States. And some leaders in South Korea have used their strategic economic partner is the PRC and their strategic defense partner security ally is the US. So that is a is a flawed approach in my mind. So we disagree with the government of certainly my time there. I haven't been there in a year, but we we disagree with Seoul on different specific issues with regard to the PRC. But in a macro sense, South Korea is our ally and we are their ally. And I think that the security relationship and our alliance relationship remains strong. But we do disagree with regard to their approach and our approach, their approach in Seoul and our approach to the PRC, for example, the Beijing Winter Olympics that come up, we're going to boycott it diplomatically. The South Korean government has said they will not do that. And there are a number of other issues, human rights issues, in the United Nations, where we'll take a stand or criticize the PRC. Other countries will join us in that effort or we'll join the EU and its effort. And South Korea, our ally, is an outlier in that regard because of their economic relationship with the PRC.

Gen. Abrams: [00:36:50] I think militarily there is very little disagreement. I think militarily we see it the same way. But as Ambassador Harris appropriately and accurately pointed out, this is dominated by the economic element of national power being leveraged by the Communist Chinese Party and the PRC. And I would tell you, Madam Ambassador, I think they are in a chokehold. And the most disconcerting things that the Chinese apply, that pressure, however they see fit.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:37:26] The US alliance structure is a critical component of our free and open Indo-Pacific strategy. Among the key groupings are the Quad or the quadrilateral security dialogue between the US, Japan, India and Australia and AUKUS the new trilateral security pact between the US, the UK and Australia. I wanted to ask you both how do relationships in the Indo-Pacific, like the Quad or AUKUS, affect Korea and the US Korean relationship?

Amb. Harris: [00:37:57] I'm a big advocate of the Quad. I called for its resurgence in 2016 at the Resident of Dialogue, the first resident of dialogue in India when I was PACOM commander. The issue with South Korea is should the Quad become a quint? And if it becomes a quint, should South Korea be the fifth member? And so it's a little push-pull, if you will. South Korea hasn't said they want to become a member of the Quad and on the pulling part of it, there's no clearinghouse for it. There's no gatekeeper for the Quad. America is not the gatekeeper. It could be Australia, it could be India, it could be Japan, it could be us. So I've called officially, publicly, I've called for the establishment of an official Quad secretariat headquartered somewhere in Asia and the Indo-Pacific in order to get at this issue of how do you bring in new members and what issues should they take on? I was very happy that right after the Biden administration took over, they had a Quad leaders meeting and happily the first issue was COVID: COVID distribution, vaccination distribution, vaccination production and that kind of stuff. Not military at all, not security at all. But I will emphasize the Quad is not NATO, is never designed to be a NATO, and it's not a defense pact. AUKUS, on the other hand, the Australia UK, United States Agreement pact is a defense pact and I'm excited about it. This is about improving Australia's capability in the Indo-Pacific. I can't wait to see an Australian nuclear submarine underway under Australian colours. So we're in the globe and I think it's exciting.

Gen. Abrams: [00:39:31] From a military perspective, I don't see anything but positives of the Quad and AUKUS specifically because I think it sends a clear message of not only the United States commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific but other like minded nations, and I think that's reassuring to the Koreans that it's not just the US that are in for the long haul. There are others like minded nations that are also in for the long haul, that share the same values, same security concerns and are linked together. But I would say on the alliance structure, and I'm not suggesting as a future treaty alliance, but from a Korean perspective and our perspective, the most important thing is the relationship between Korea, Japan and the United States, and that's focused principally on Northeast Asia. And that's something that transcends administrations. It's something that I experienced when I was working for the Secretary of Defense in the Obama administration. And I certainly saw the continued importance of it in the Trump administration. Of course, we see it now in the Biden administration. But for that trilateral relationship to proceed to the next level, two of the partners, three in Japan, will have to find some resolution and reconciliation on their very complicated history.

Amb. Harris: [00:40:52] And I'll just close on this issue, and that is that I couldn't say what I was in uniform or in service. I can say it now. My personal belief is that the Quad and AUKUS are focused on the PRC. And so therein lies the rub for a country like South Korea, which is trying to straddle the fence. So if we were to increase the Quad to the Quint or whatever six is, and Latin and seven and eight and nine and ten, will South Korea be that system? I don't know that. What about Indonesia? What about Malaysia? What about the UK? What about France? Who has a large presence in the Pacific? I think that if not publicly, certainly privately, but officially, South Korea needs to let the United States know that it wants to be a member, and then then we can figure out the modalities of how to make that work in concert with the three other members of the Quad.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:41:49] To wrap up, I wanted to ask a few questions related to your tag teaming in South Korea, and I have two for you, Harry. The first one is what was the biggest adjustment for you in moving from being an active duty senior military officer to being a US ambassador?

Amb. Harris: [00:42:06] I think the biggest difference is scale. INDOPACOM of 400,000 people, 400,000 troops and all of that at the American embassy and so 400, so a slightly different scale. But I will tell you that the amount of effort on my part, since the question is about me, was the same. My workday was as long as I was involved in Seoul as it was in Hawaii. But the difference, of course, in that regard is I was focused on Korea and North Korea, 365 days, 24 seven. So I knew a lot about the issues on the Peninsula. At INDOPACOM, I knew a little about a lot. So it was more of a peanut butter spread approach. But I will also say that that I learned quickly that the dedication and the commitment and the courage of young Foreign Service officers is significant. And the military holds no monopoly on courage, dedication and commitment. So we have these young Foreign Service officers, civil service officers in embassies abroad that are doing hard things on their own and in many cases in combat zones. Korea is not one per se, but combat zones on their own, not backed up by a battalion landing team or a day combat team or anything like that. And we ask a lot of these young Americans, both in the Foreign Service and in the uniformed services. And so I was proud to serve with them, just as I was proud to serve with my colleagues in uniform.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:43:38] Well, you left a year ago. We still do not have a new ambassador name. How does this affect us effectiveness on the ground with this key ally?

Amb. Harris: [00:43:48] I think it's important to have an ambassador in country, especially in those countries that are allies and in those countries that are adversaries, because you need to have that direct relationship that an ambassador is supposed to have as chief of mission and as the president's woman or man on the spot. The White House has not nominated an ambassador to Korea, one of our key security allies, one of our key economic partners in a global force for good across the world. We have not nominated an ambassador to Korea yet. So I'm disappointed and I'm hopeful that we'll get a quality nominee soon.

Gen. Abrams: [00:44:30] I'd say two things. And the first one I feel very strongly about. I won't be on the record with you, Ambassador. Ambassador Harris had an awesome embassy team and the teamwork between his staff and our U.S. forces Korea staff could not have been better. But I give all credit to Ambassador Harris, who clearly had made that a priority inside the embassy, and it permeated and it allowed us to operate at the speed of relevance in information sharing so that the US military side, US forces Korea. We were not surprised by what was happening on the Department of State side. And likewise, I never wanted the ambassador or the mission to be surprised by something that it was emergent in the military domain, whether that be on pen, something from the Department of Defense, something from INDOPACOM. But he had a crack staff.

Amb. Harris: [00:45:31] You know, we didn't talk about COVID. This the last year of my time there was all about COVID. And we would not have survived literally were it not for us medical department. The embassy had a great doc, but it was one doc and two nurses, two Korean nurses and one American nurse. But we relied on USFK's medical staff and their doc was actually an epidemiologist by training infectious disease guy, and we literally live because of USFK Medical and that was General Abrams Abe, who opened it up to us to use and rely on their expertise, put us in all of their message traffic, cable traffic and all of that. So it was significant.

Gen. Abrams: [00:46:18] On the other question, and this is nothing against the charges, but in my view, when you don't have a card carrying ambassador who carries the full weight as chief of mission, it does have an impact. There's only so much that a chargé can do. And no matter how good the chargé is, their counterparts in the Foreign Ministry, in the Blue House and other places, they just don't they don't feel the weight. Ambassador Harris has shown a number of exemplars of where when he used his weight, the position, he would generate a response, his attention.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:46:57] Abe, I wanted to ask you one last question. As you wore your tri commander hat, what was the biggest diplomatic challenge surprise that you encountered in your time there?

Gen. Abrams: [00:47:10] I had done a lot of self study before I went. I actually spoke to all seven living predecessors of mine, some 2 to 4 hour long conversations to help shape my approach and so forth. And so. Having not served in Korea before, I wanted to make sure that I was appropriately prepared for what I was about to get into, and all of them contributed to help paint that picture. I think even though they had all told me this. What surprised me was the significance that the senior US military officer in Korea. The significance that that position has inside the Republic of Korea. I had already been an Army four star for three years, commanded the largest organization in the Department of Defense for three years at US Army Forces Command. I'd given countless speeches, remarks, been all over the country, and I can honestly say that my name might have appeared in the media three times in three years as the FORCECOM Commander in Korea. That position holds so much significance because of its connection through the years back to the very beginning that when the senior US military officer in Korea speaks, everybody listens.

Gen. Abrams: [00:48:30] And I could give a short five minute set of remarks, opening remarks at some conference or something like that, and I'd be on the evening news and on the front page of the morning papers the next day above the fold. And so diplomatically, that means that the senior US officer there has to straddle. I'm there certainly as the combined Forces command commander to lead the alliance's defense efforts if the war was to restart from an operational warfighting perspective. But the role straddles that. And so that's why I was so important for me to be very closely in tune with Ambassador Harris and the embassy of the Department of State, because many of the things that I would say publicly, regardless of the topic, always had a diplomatic impact potentially, and Ambassador Harris or one of his people would hear about it. And if I'd say something publicly and the next day they'd be getting ten questions from the foreign ministry. Hey, what did General Abrams mean by that? And so I guess it's got an outsized impact. That was a bit surprising. I've been forewarned, but that was probably the most surprising.

Amb. McCarthy: [00:49:43] Gentlemen, thank you for being the team on the ground in those critical years. Thank you for joining us and explaining what military leaders do, what our diplomatic leaders do. This has been a terrific conversation. I really appreciate it. So thank you. Thank you very much. Our series is a production of the American Academy of Diplomacy in partnership with UMC Global at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. You can find our podcasts on all sites and on our website. Www.GeneralAmbassadorPodcast.org. We welcome feedback and suggestions and can be reached at General.Ambassador.podcast@gmail.com. We do answer the mail. Thank you for listening.